(单词翻译:单击)

听力文本

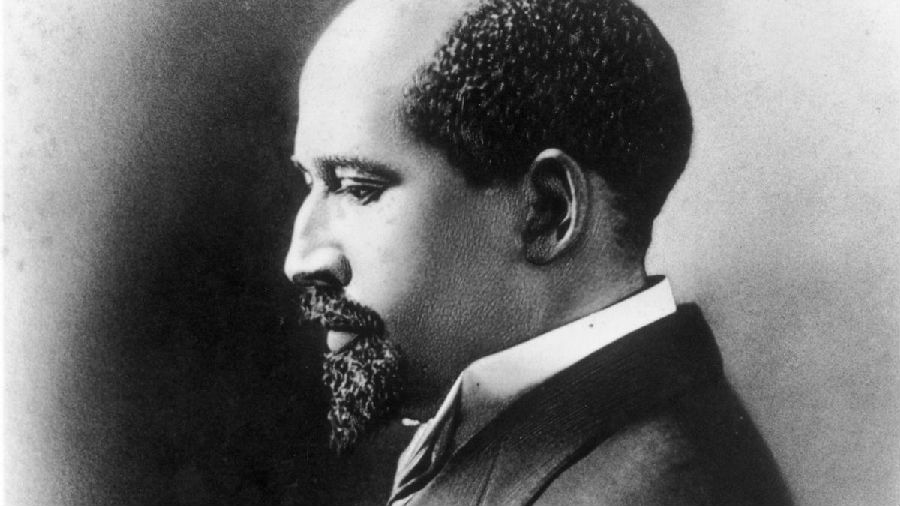

I'm Steve Ember. And I'm Sarah Long with the VOA Special English program PEOPLE IN AMERICA. Today we tell about W.E.B. Du Bois. He was an African-American writer, teacher and protest leader.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois fought for civil rights for black people in the United States. During the nineteen twenties and nineteen thirties, he was the person most responsible for the changes in conditions for black people in American society. He also was responsible for changes in the way they thought about themselves.

William Du Bois was the son of free blacks who lived in a northern state. His mother was Mary Burghardt. His father was Alfred Du Bois. His parents had never been slaves. Nor were their parents. William was born into this free and independent African-American family in eighteen sixty-eight in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. William's mother felt that ability and hard work would lead to success. She urged him to seek an excellent education. In the early part of the century, it was not easy for most black people to get a good education. But William had a good experience in school. His intelligence earned him the respect of other students. He moved quickly through school. It was in those years in school that William Du Bois learned what he later called the secret of his success. His secret, he said, was to go to bed every night at ten o'clock.

After high school, William decided to attend Fisk University, a college for black students in Nashville, Tennessee. He thought that going to school in a southern state would help him learn more about the life of most black Americans. Most black people lived in the South in those days. He soon felt the effects of racial prejudice. He found that poor, uneducated white people judged themselves better than he was because they were white and he was black. From that time on, William Du Bois opposed all kinds of racial prejudice. He never missed a chance to express his opinions about race relations. William Du Bois went to excellent colleges, Harvard University in Massachusetts and the University of Berlin in Germany. He received his doctorate degree in history from Harvard in eighteen ninety-five. His book, "The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study," was published four years later. It was the first study of a black community in the United States. He became a professor of economics and history at Atlanta University in eighteen ninety-seven. He remained there until nineteen ten.

William Du Bois had believed that education and knowledge could help solve the race problem. But racial prejudice in the United States was causing violence. Mobs of whites killed blacks. Laws provided for separation of the races. Race riots were common. The situation in the country made Mister Du Bois believe that social change could happen only through protest. Mister Du Bois's belief in the need for protest clashed with the ideas of the most influential black leader of the time, Booker T. Washington. Mister Washington urged black people to accept unfair treatment for a time. He said they would improve their condition through hard work and economic gain. He believed that in this way blacks would win the respect of whites. Mister Du Bois attacked this way of thinking in his famous book, "The Souls of Black Folk." The book was a collection of separate pieces he had written. It was published in nineteen-oh-three.

In the very beginning of "The Souls of Black Folk" he expressed the reason he felt the book was important: "Herein lie buried many things which if read with patience may show the strange meaning of being black here at the dawning of the Twentieth Century. This meaning is not without interest to you, Gentle Reader; for the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line. " Later in the book, Mister Du Bois explained the struggle blacks, or Negroes as they then were called, faced in America: "One ever feels his twoness -- an American, a Negro: two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideas in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. ... He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly in his face." W.E.B. Du Bois charged that Booker Washington's plan would not free blacks from oppression, but would continue it. The dispute between the two leaders divided blacks into two groups – the "conservative" supporters of Mister Washington and his "extremist" opponents.

In nineteen-oh-five, Mister Du Bois established the Niagara Movement to oppose Mister Washington. He and other black leaders called for complete political, civil and social rights for black Americans. The organization did not last long. Disputes among its members and a campaign against it by Booker T. Washington kept it from growing. Yet the Niagara Movement led to the creation in nineteen-oh-nine of an organization that would last: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Mister Du Bois became director of research for the organization. He also became editor of the N.A.A.C.P. magazine, "The Crisis." W.E.B. Du Bois felt that it was good for blacks to be linked through culture and spirit to the home of their ancestors. Throughout his life he was active in the Pan-African movement. Pan-Africanism was the belief that all people who came from Africa had common interests and should work together in their struggle for freedom.

Mister Du Bois believed black Americans should support independence for African nations that were European colonies. He believed that once African nations were free of European control they could be markets for products and services made by black Americans. He believed that blacks should develop a separate "group economy." A separate market system, he said, could be a weapon for fighting economic injustice against blacks and for improving their poor living conditions. Mister Du Bois also called for the development of black literature and art. He urged the readers of the N.A.A.C.P. magazine, "The Crisis," to see beauty in black. In nineteen thirty-four, W. E. B. Du Bois resigned from his position at "The Crisis" magazine. It was during the severe economic depression in the United States. He charged that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People supported the interests of successful blacks. He said the organization was not concerned with the problems of poorer blacks.

Mister Du Bois returned to Atlanta University, where he had taught before. He remained there as a professor for the next ten years. During this period, he wrote about his involvement in both the African and the African-American struggles for freedom. In nineteen forty-four, Mister Du Bois returned to the N.A.A.C.P. in a research position. Four years later he left after another disagreement with the organization. He became more and more concerned about politics. He wrote: "As...a citizen of the world as well as of the United States of America, I claim the right to know and think and tell the truth as I see it. I believe in Socialism as well as Democracy. I believe in Communism wherever and whenever men are wise and good enough to achieve it; but I do not believe that all nations will achieve it in the same way or at the same time. I despise men and nations which judge human beings by their color, religious beliefs or income. ... I hate War." In nineteen fifty, W. E. B. Du Bois became an official of the Peace Information Center. The organization made public the work other nations were doing to support peace in the world.

The United States government accused the group of supporting the Soviet Union and charged its officials with acting as foreign agents. A federal judge found Mister Du Bois not guilty. But most Americans continued to consider him a criminal. He was treated as if he did not exist. In nineteen sixty-one, at the age of ninety-two, Mister Du Bois joined the Communist party of the United States. Then he and his second wife moved to Ghana in West Africa. He gave up his American citizenship a year later. He died in Ghana on August twenty-seventh, nineteen sixty-three. His death was announced the next day to a huge crowd in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Hundreds of thousands of blacks and whites had gathered for the March on Washington to seek improved civil rights in the United States. W. E. B. Du Bois had helped make that march possible.

重点解析

1.fight for 为…而战,而奋斗

He readied himself to fight for freedom. 跟读

他准备为自由而战斗。

2.lead to 导致;通向

A lack of prudence may lead to financial problems.

不够谨慎可能会导致财政上出现问题。

3.earn 赚,赚得;获得

Companies must earn a reputation for honesty.

公司必须赢得诚信。

4.prejudice 偏见

There was a deep-rooted racial prejudice long before the two countries went to war.

早在两国交战之前就有了根深蒂固的种族偏见。

5.uneducated 无知的;未受教育的

Rumours are easily spread among uneducated people.

谣言容易在无知的人中间传播。

6.unreconciled 未和解的;未取得一致的

The enemies are unreconciled to their defeat.

敌人并不甘心失败。

参考译文

我是史蒂夫·恩贝尔。我是莎拉·朗。这里是VOA慢速英语栏目《美国人物志》。今天我们将讲述W.E.B.杜博斯的故事。他是一名非裔美国作家、老师也是抗议领袖。威廉·爱德华·布格哈特·杜博斯在美国为黑人民权而奋斗。20世纪20到30年代,他为改变美国黑人的生活条件,改变他们对自己的认知做出了很大的贡献。威廉·杜博斯是自由黑人的儿子,他们住在北部。他的母亲是玛丽·布格哈特,他的父亲是阿尔佛雷德·杜博斯。他的父母都没当过奴隶,他们的长辈也没有。

1868年威廉出生在这个位于马萨诸塞州大巴灵顿的自由独立的非裔美国家庭。威廉的母亲认为能力和努力可以获得成功。她力劝威廉寻求更好的教育。在这个世纪早期,黑人要获得好的教育并不容易。但威廉在学校有着不错的经历。他的聪明才智威廉赢得了其他学生的尊重。他很快适应了学校。正是在学校的那些年,威廉·杜博斯学到取得成功的秘诀。他说,他的秘密是每晚十点上床睡觉。高中毕业后,威廉决定去费斯克大学,这是一所位于田纳西州那什维尔的黑人大学。他认为在南方州读书能够帮助他了解更多大部分美国黑人的生活。那时,大部分黑人都生活在南方。很快他就感受到了种族偏见的影响。他发现那些贫穷且未接受过教育的白人瞧不起他,就因为他们是白人,而他是黑人。从那时起,威廉·杜博斯反对所有形式的种族偏见。他从未错过任何一次表发关于种族关系言论的机会。

威廉·杜博斯去了几所很好的大学—马萨诸塞州的哈佛大学以及德国的柏林大学。1895年,他在哈佛大学获得历史系博士学位。他的书籍《The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study》于四年后出版。这是美国第一本研究黑人社会的书。1897年,他成为了亚特兰大大学的一名经济历史学教授直到1910年。威廉·杜博斯认为教育和知识可以帮助解决种族问题。但美国的种族偏见引发了暴力。暴乱的白人杀害黑人。法律要求种族隔离。种族暴乱普遍存在。国内的状况让杜博斯相信只有通过反抗才能获得社会的变革。

杜博斯相信的反抗和当时最有影响力的黑人领袖布克·华盛顿的想法不同。华盛顿要求黑人接受那时对他们的不公正对待。他说他们要通过努力工作和经济成果来改善他们的情况。他认为通过这种方式黑人能够赢得白人的尊重。杜博斯在《The Souls of Black Folk》一书中抨击了这种想法。这本书收集了他写过的作品,出版于1903年。在《The Souls of Black Folk》开篇,他表达了他认为这本书很重要的原因:“如果你耐心读完这本书,你会发现在20世纪初,成为黑人的奇怪意义。亲爱的读者,这种意义能够引起你的兴趣,因为20世纪的问题就是种族界限的问题。”在这本书结尾,杜博斯解释了黑人在美国面临的挣扎:“一个人感觉自己有两种身份—一名美国,一名黑人:两个灵魂,两种思想,两种无法调和的斗争;在一个黑暗的躯体中的两种敌对思想,仅依靠躯体中顽强的力量阻止他被撕成碎片...他仅仅希望一个人可以即是黑人也是一名美国人,不受诅咒,不被同胞鄙视,不用面对机会失去的情景。”

W.E.B.杜博斯认为布克·华盛顿的计划无法将黑人从压迫中解救出来,只会让这种压迫继续。两位领袖之间的争吵让黑人分成了两派—华盛顿的‘保守’支持者以及他的‘极端’反对者。1905年,杜博斯成立尼亚加拉运动组织反对华盛顿。他和其他黑人领袖要求美国黑人拥有完整的政治、公民以及社会权利。这个组织并没有持续多久。其成员之间的争端以及华盛顿领导的反对该组织的运动阻碍了它的成长。但是尼亚加拉运动组织促成了1909年另一个组织的成立:美国全国有色人种协进会(N.A.A.C.P.),这个组织长存了下来。杜博斯成为该组织研究部主管。他还成为了N.A.A.C.P.杂志《The Crisis》的编辑。

W.E.B.杜博斯认为让黑人通过文化和精神与祖先相联系是件好事。他一生都活跃在泛非运动中。泛非洲主义认为来自非洲的所有人都有共同的利益,应该在自由之战中共同合作。杜博斯认为美国黑人应该支持欧洲殖民地上非洲国家的独立。他认为一旦非洲民族脱离欧洲的控制,他们可以成为美国黑人产品和服务的市场。他认为黑人应该发展独立的‘集体经济’。一个单独的市场体系,他说,可以成为抗击经济不公,改善生活状况的武器。杜博斯还要求发展黑人文化和艺术。他要求N.A.A.C.P.杂志《The Crisis》的读者发现黑的美。1934年,W.E.B.杜博斯从《The Crisis》杂志辞职。那时正好是美国经济萧条期。他指责美国全国有色人种协进会支持成功黑人的利益。他说该组织不关心穷苦黑人的问题。

杜博斯回到从前教书的亚特兰大大学。接下来的十年,他都在那里教书。在此期间,他写了自己参与非洲人以及非裔美国人自由运动的经历。1944年,杜博斯回到N.A.A.C.P.研究调查岗位。四年后,与该组织再次产生歧义后,他离开了。他变得越来越关注政治。他写道:“作为世界一员,美国一员,我有权知道、思考并讲述我看到的事实。我相信社会主义和民主主义。我相信共产主义,不论何时何地,只要人们有智慧和优秀品质就能实现它;但是我不相信所有民族都会在同一时间以同样的方式获得成功。我鄙视那些通过肤色、种族信仰或是收入判断别人的人和国家...我恨战争。”

1950年,W.E.B.杜博斯成为和平信息中心的官员。该组织公布其他国家为支持世界和平而做的工作。美国政府指责该组织支持苏联并起诉其官员是外国间谍。一名联邦法官发现杜博斯是无辜的。但是多数美国人还是认为他是一名罪犯。他被无视对待。1961年,92岁的杜博斯加入美国共产党。然后他和他的第二任妻子搬到了西非的加纳。一年后,他放弃了他的美国国籍。1963年8月27日,他在加纳去世。在他去世后第二天,在华盛顿林肯纪念堂前,他的死讯被公之于众。数万名黑人和白人聚集华盛顿要求改善公民权利。W.E.B.杜博斯使这次聚集游行成为可能。

译文为翻译,未经授权请勿转载!